Mayavase.com Research Material

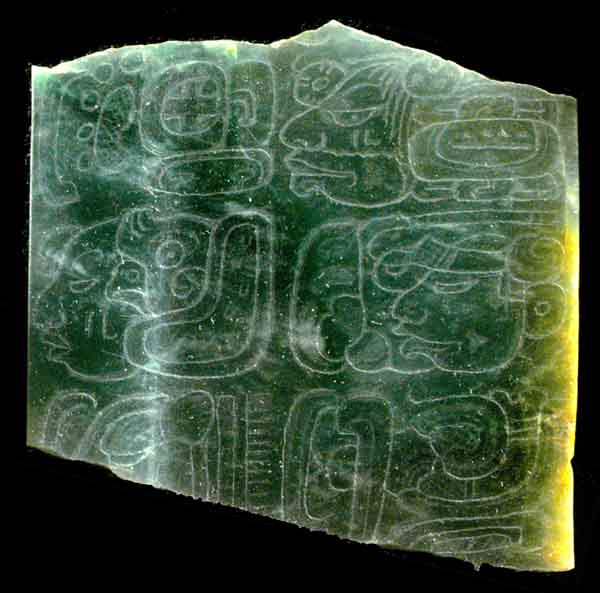

Comments on a Celt Fragment

Comments from David Stuart

Structurally the text beaks down as a possessed noun (an odd one – U-HUL?-K’AN-mu-li) followed by a woman’s name. The initial title (at Bp1) is an early example of a fascinating “ring number” term that appears with women’s names at Dos Pilas, Naranjo and Tikal, among other sites. Interestingly, the numbers change among the known examples: here it’s “9” but at Dos Pilas (on Throne 1) it’s a “3” if I recall. Somebody needs to brings these together into a nice little study of some sort. The woman’s name is based on K’UK’ followed by an odd bent sign (other examples, anyone?), and then MO’-NAAH-AJAW (“Macaw House Lord”). We then get U-BAAH-AJ (not the absolutive ending, clearly) and another possessed noun written with the “axe” and the curious spiral element — weird stuff. I wonder though if this last combo is related to the “axe-ohl” sequence found in later texts in Yucatan and on Merwin’s Holmul plate.

Comments from Steve Houston

I have only a few things to add to Dave's comments:

By having images of the other side, we now know that this is *not* a fragment of another fragmented celt (St. Louis?) -- the standing image on the other side clinches this point. But the similarities are strong, nonetheless: we have what is probably the same [U-HUL?-?] (probably linked in some fashion to the 7/9 pairs in Maya iconography) at B4 on the other celt. This must surely be the glyph at upper-left on the K8749 celt. Note that the position is more-or-less the same in the text, suggesting that we are dealing with a formula that is distinct to these adzes. In fact, I think it would be a great project for a graduate student to "collect" these adzes and examine them as a category.

** I have little doubt that there is a woman's name on the K8749 celt. As Dave points out, the title at pB1 is one that is used, especially in Late Classic settings, in connection with royal ladies. However, as Dave also remarks, these are not all the same: the one at Dos Pilas has a 3, those at Tikal and Naranjo a 6. There is a strong suspicion that these "bundled numbers" are related in some way an unusual number (in this case 8) that appears in the codices and at Copan -- an allusion to the Maize God/Goddess, the usual head variant of the number 8? I may be in slight disagreement with Dave about the female head at pB1, as it is probably a conflation of the "wind god head" (#3) with, perhaps, the expected female head. In two of the Late Classic examples the "bundled numbers" have, among other things, a river-serpent sign in this position. It is odd, I think, that such mention is made on the text and yet, evidently, the figure on the other side is a male.

** The quetzal head at pA2 is couched in, as Dave says, a very odd sign. The markings are those of cotton, I believe -- is this a kind of nest, patched together, as birds do, from vegetal material? Is there a couplet present the celt? Quetzal-"home"/Macaw-"structure"?

** To play Devil's advocate, I have become a little leery about the Ajaw signs in earlier settings. We have been struggling over the last few years against what I have called the "synoptic fallacy," that of seeing a more-or-less coherent and unchanging writing system. We now know, increasingly, that this "synopticism" has helped us in decipherment but has also led to interpretive problems. As a thought experiment, I went over my meager collection of early Ajaw signs, and they are quite a mess: one doesn't see patent substitions with the 1 Ajaw until relatively late, and many of these do not have earspools. That is, the free substitutions we take for granted do not materialize in the rather rigid distinctions made in the earliest texts. When, for example, does Floyd's "ah po? (T168) begin to take clear suffixation? What I'm suggesting is that it might be useful for us collectively to look closely at the chronology of these developments. The free substitutions may be a fairly late phenomenon. An early "Ajaw" head, for example, appears to be the Chicchan sign -- when do we see the merger with the Ajaw day sign per se?

** These 'baah' signs, I think we all agree, have to mean something like "materialized body." They also, from an early period, refer closely to celts, probably in their role as bodily substitutes. This practice even goes up into the Late Classic period, when we see "celt-bodies" being lugged around, and as mentioned on Piedras Negras Throne 1. (There's a nice "first resting" intransitive, in fact.) The k'an in the cheek is very clear on the K8749 celt, and I would suspect that the /a/ is, as Dave says, not the absolutive but his "person" sign. A similar kind of connection between precious objects and this expression occur on the back of the Rio Azul mask. Of course, the sign at pB3 has, as Dave points out, clear parallels with the expression that occurs throughout the Maya area, even up to Chichen, in the Akab Dzib.

Comments form Luis Lopes

I would just like to comment Stephen Houston's suggestion that the Quetzal "hanging" in the strange /no/ or /le/ -like deformed glyph might represent a nest, in this case a bird nest.

Just out of curiosity I checked the Odense Online Maya Dictionary and discovered that the word for "birdnest" in many maya languages is k'u' for example, Laca, Yuc, Itza, Mop, Chol, Chon.

This may mean that the quetzal head is there really acting as a phonetic prefix /k'u/ to the entire compound. So maybe here: ixik k'u' is the intended reading.

There is at least another example of a possibly similar name from lady. This is in Altar 5 from Tikal where you have: u-BAAHK-JOL TSIK?-la-K'UH-IXIK IXIK-YAX-"bird head"-le?/"cotton glyph" WAYIS-si

This "bird head" resting on this /le/-like glyph may indeed be a latter form of the birdnest glyph, rather than a phoneme here.